In the small town of Beawar in Rajasthan, where the sun beats down on dusty roads and people still remember the old fights for their rights, something big happened again. Hundreds of people came together at the first national RTI fair, or mela as they call it. This was not just a celebration. It was a call to action. Famous activists like Aruna Roy, former judge A.P. Shah, and India’s first Chief Information Commissioner Wajahat Habibullah spoke up. They said the new Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) law is hurting the Right to Information (RTI) Act. They want people to understand their power and fight back. “The key to government is in the hands of the people. They must know their strength,” said Shah. This event marks 20 years since the RTI Act became law on October 12, 2005. But now, from the same land where RTI was born, a new battle starts against laws that hide information.

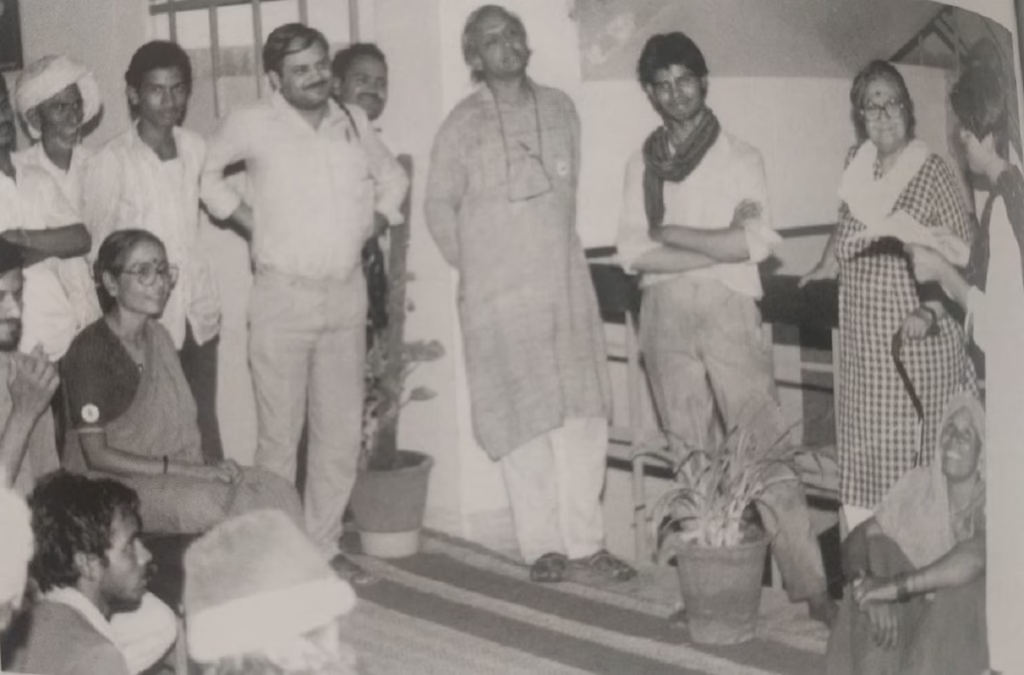

The RTI mela was held at Narbadkheda in Beawar district. It was organized by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), a group that has been fighting for workers’ and farmers’ rights for years. People from all over India came – from Telangana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and even far places like Jammu and Kashmir. They talked about how RTI has changed lives, but also how the government is trying to weaken it. On Saturday evening, thousands marched through Beawar’s streets, just like the old protest in 1996. That was when people sat for 40 days at Chang Gate, demanding to see government records. Songs were sung, stories shared, and everyone felt the spirit of those old days.

Aruna Roy, who won the Magsaysay Award for her work, was at the center of it all. She is from MKSS and has spent her life in villages, helping poor people get what they deserve. “The DPDP law is an attack on transparency and accountability through changes to the RTI Act,” she said. “We need to start a new movement from Beawar’s soil.” Roy remembered how RTI started. In the 1990s, workers wanted to see muster rolls – lists of who worked on government projects and how much they got paid. Many times, money was stolen, and names were fake. People like Sushila Devi, a 60-year-old woman from a village near Beawar, went door to door asking for support. She faced threats but got the records after a month. It showed half the workers were not paid. This small win led to big changes, like making hospitals show lists of free medicines. Before, doctors sent people to buy from shops, but now everyone knows what’s available.

Roy’s words touched everyone. She said RTI is not just a law from Parliament. It came from people’s struggles. “Governments fear accountability,” she added. “They are making information commissions like puppets.” In her interview with a magazine, she explained how RTI has been slowly broken – by changing how commissioners are picked, their pay, and even their time in office. “It’s both in words and in action,” she said. The DPDP Act is the worst, she thinks. It says personal data can’t be shared without permission, but this can hide corruption. For example, names of big loan defaulters or who bought electoral bonds might stay secret.

Former judge A.P. Shah, who was once the chief justice of Delhi High Court, agreed. He has spoken a lot about privacy and rights. “RTI gave people the key to open locked boxes of power,” he said at the mela. “Now, governments want to close them again.” Shah pointed out that Section 8 of RTI already protects privacy. But DPDP goes too far. It’s against the Constitution, he believes. In an open letter earlier this year, he asked to cancel the changes to RTI. “People’s power made RTI, and no one can kill it easily. But these tries to weaken it – no village council has spoken against them yet,” he said.

Wajahat Habibullah, the first person to lead the Central Information Commission, was also there. He helped make RTI work in its early days. “For the first time, people came to the center of governance with RTI,” he told the crowd. “But power wants to limit it again. Why don’t you fight back? This is my complaint. Since people gave birth to this right, they must protect it.” Habibullah warned that if RTI gets weak, democracy’s openness will end.

Other people spoke too. Nikhil Dey from MKSS said they faced jail and beatings in the old days, but villagers supported them. “It was a people’s movement, especially from rural areas,” he said. Kavita Srivastava from People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) called RTI the backbone of democracy. Nikhil Dey from the farmers’ group talked about needing a law for accountability. Rakshita Swamy from a research forum supported it.

The mela was not just talks. There were exhibitions showing old posters, songs, and stories from the RTI fight. Young people promised to go to villages and teach about government plans. They want to make RTI stronger. And there was a big moment – laying the foundation for India’s first RTI museum at Narbadkheda. Architect Anu Mridul said the theme is “From Opacity to Transparency.” They will use local soil and materials. The museum will keep memories of the movement – documents, photos, and tales of bravery.

Why is everyone so worried about DPDP? Let’s explain simply. The DPDP Act came in 2023 to protect personal data, like your name, address, or phone number. That’s good, right? But it changes RTI’s Section 8(1)(j). Before, you could get personal info if it was for public good, like exposing a scam. Now, it’s a full stop on personal info. Critics say this helps hide bad things. For example, if a leader has wrong assets, or a company cheats, names might not come out. Anjali Bhardwaj from NCPRI says it’s a blanket ban. Apar Gupta from Internet Freedom Foundation thinks it hurts press freedom too. Journalists might need permission to use data, or face big fines.

Even opposition leaders like from Congress say Modi government is killing RTI. “It guts the public interest part, using privacy to hide corruption,” they say. But the government says it’s balancing privacy, as per Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy judgment on right to privacy. Attorney General backs it, saying it doesn’t weaken RTI.

From Beawar, the message is clear: People must wake up. Like in 1996, when a simple demand for wages led to a national law. Sushila Devi’s story shows how one person can start change. She got threats but kept going. Today, RTI has helped millions – over 50 lakh applications a year. It exposed big scams, made governments answer. But if DPDP stays like this, many doors will close.

Ashok Gehlot, former Rajasthan CM, called RTI a historic step. “It empowers citizens and makes rule clear,” he said. But he blames the center for leaving commission posts empty and cutting powers.

The mela ended with hope. Songs like “Main nahi maanga, mera haq maanga” echoed. People left feeling strong. Beawar, once a quiet town, is again the start of something big. Will this new fight win? Only if common folks join, like before.

What Others Say

- Opposition MPs in a letter: “Repeal Section 44(3) of DPDP. It weakens fundamental right to know.”

- Amrita Johri, NCPRI: “Blanket restraint on personal info removes safeguards.”

- Lal Singh, activist: “Right to know is like right to life. Without info, rights are broken.”

FAQs on RTI and DPDP Conflict

What is the RTI Act?

The Right to Information Act, 2005, lets any Indian ask for info from government offices. You pay Rs 10 and get answers in 30 days. It started from grassroots fights in Rajasthan to stop corruption. Over years, it has made governments more open. More than 50 lakh people use it every year to check things like school funds or road work. It’s like a tool for common people to hold power accountable.

What is the DPDP Act?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, is India’s law to protect personal data online. It says companies and government must handle your info carefully, get consent, and prevent leaks. But it has rules for fines up to Rs 250 crore if broken. The goal is privacy, but critics say it gives too much power to government and hurts openness.

How does DPDP affect RTI?

DPDP changes RTI’s Section 8(1)(j). Before, personal info could be shared if public interest was bigger, like in corruption cases. Now, it’s fully exempt. This means names in scams, loan lists, or leader’s assets might stay hidden. Activists say it’s a way to shield wrongdoers. It wasn’t in early drafts but added later without much talk. This could make RTI weak and hurt journalism too, as reporters might face fines for using data.

Why start the fight from Beawar?

Beawar is where RTI began in 1996 with a 40-day protest by MKSS. People demanded to see records to fight corruption. It led to Rajasthan’s RTI in 2000 and national law in 2005. Now, for DPDP, it’s the same place to restart because it shows people’s power. Aruna Roy said, “The movement started here, so the new one will too.”

What can common people do?

File more RTIs to keep the law alive. Join groups like MKSS or NCPRI. Spread awareness in villages. Support calls to change DPDP. As Habibullah said, “People gave birth to RTI, they must save it.”

Is privacy more important than transparency?

Both are needed. Supreme Court said privacy is a right, but RTI balances it with public good. DPDP tips the scale too much to privacy, say experts. It could hide corruption while not fully protecting data from big companies or government spy.